Last year, I started writing a list of things that make me happy, or at least make me feel a bit better: small things that I can offer myself as acts of self-care, like dancing, good food, hugs, crying, putting on the dark lipstick that I love, hiding in bed for days, and drinking tea by the sea.

Numerous ads and pictures and videos are splashed all over Instagram and the internet showing a beautiful girl standing at a big window in a beautiful house, drinking tea and looking out over green mountains in the distance, with a smile on her face. The image is beautiful, and these words are written beneath it : “Love yourself.”

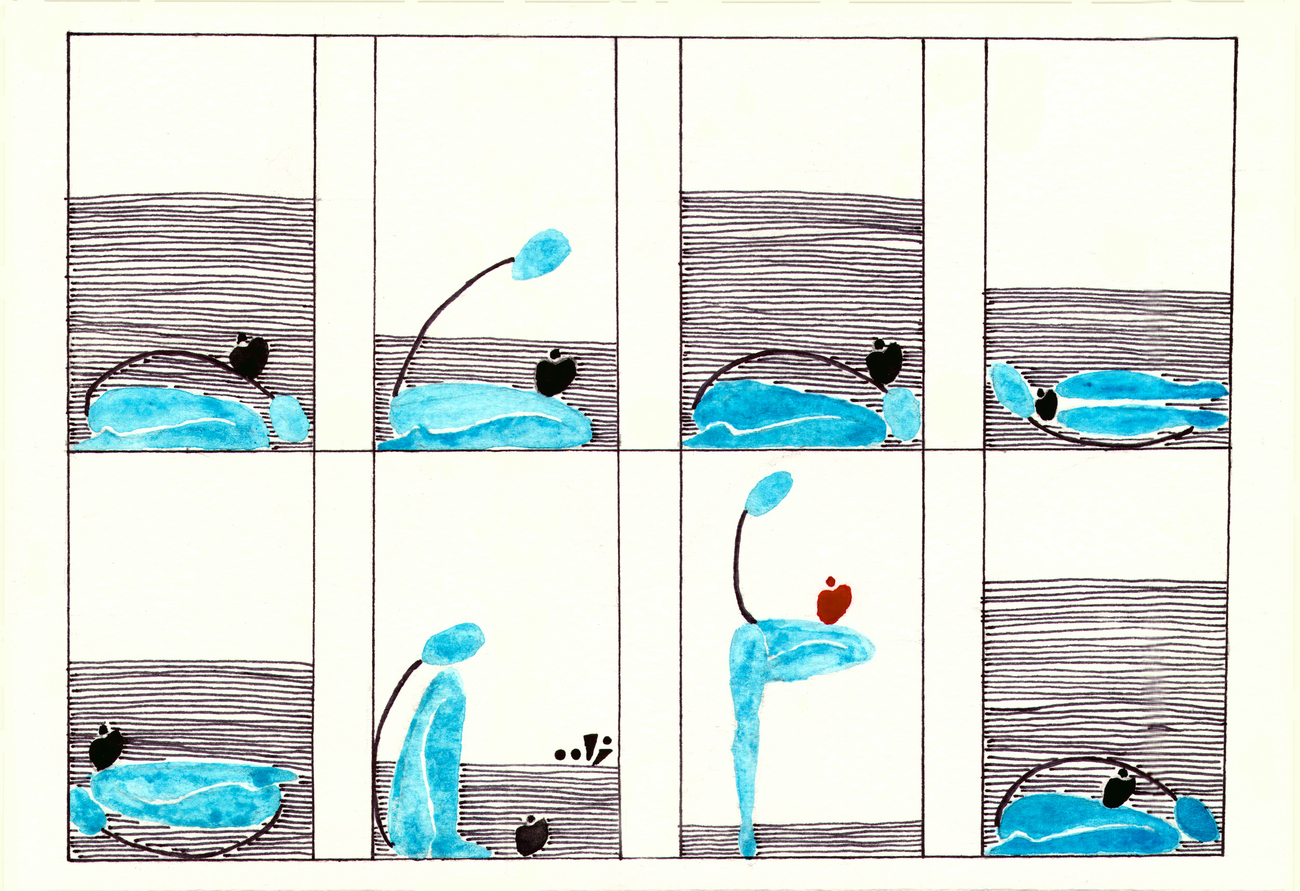

The problem with this image is that it instills in our subconscious the idea that there’s a quick fix, a happy ending, to self-love — if you just will it to be, it will be. In reality, we don’t love ourselves or experience calm and cheerful days that easily: most of the time we have to practise self-love in the darkest times, when we’re hiding under the covers after crying for hours. Even when we embrace ourselves, flowers don’t bloom, birds don’t start singing, and the clouds don’t clear.

Last year, I started writing a list of things that make me happy, or at least make me feel a bit better. Small things that I can offer myself as acts of self-care, like dancing, good food, hugs, crying, putting on the dark lipstick that I love, hiding in bed for days, and drinking a glass of tea by the sea. I wrote the list on a piece of paper and hung it up on my bedroom wall. I kept adding to it, little by little, according to what I was actually doing to take care of myself and to love myself as I am.

Looking at myself naked in the mirror was one of the items on the list, to come to terms with my appearance and learn to like it.

Some time ago, I found out from my mother that, around the age of nine, I stood in front of a mirror, looked at myself, and said: “I’m not beautiful.” I’ve come up with many theories on how I formed this idea about myself at such a young age, but it still hasn’t left me entirely. So I convinced myself to look at my naked body repeatedly in the mirror. To study my face for a long time, my neck, my mole, my breasts, my hands, and the folds in my belly when I sit down. I look at my kneecaps, my buttocks, my body hair. I’ve decided that I like my waist, my prominent collarbone, my thick black hair, the shape of my cheeks; and that I hate my right eyebrow, my toes, and my small shoulders. I declared a truce with my fingers when I found a new passion for rings. After a while, I started forgetting to look into a mirror, even when I left the house. But my childhood ideas haven’t left me entirely. They come and go, and I remind myself about the contract of love that I made with my body and appearance.

My list stood for more than my attempts at self-love. I hid behind that list a naïve wish to find a simple, guaranteed formula that I can resort to whenever I wanted to. I wanted to trick myself by finding a magic recipe, a shortcut to self-acceptance. The list carried more expectations than it could bear. I wanted it to be the solid ground beneath my doubts, a wall blocking my nihilism, a hand that could nudge me out of despair. But it was, in fact, just an attempt to remind myself of things that I love and that console me.

The image of the “happy” girl at the window also ignores the cruelty of our world. She tells me to love myself, but what about the world that doesn’t love me?

After some time, most of the things on the list stopped working. Music no longer moved me to dance, I lost my desire to put on that dark lipstick, and I stopped studying my body in the mirror. My doubts and insecurities were stronger than these positive acts. Why did the list not make me happy? Or curb my disappointment with myself? I don’t know.

The image of the “happy” girl at the window also ignores the cruelty of our world. She tells me to love myself, but what about the world that doesn’t love me? This kind of image places the full burden of responsibility, for that promised and awaited happiness, on our own shoulders.

How can a glass of tea by the sea, with Um Kulthum singing in the background, really reassure me that everything will be all right, that I will achieve something fulfilling and worthwhile, at a time when our worlds have collapsed and we can see only ruins?

My only maternal aunt opened a window inside me when she said: “Why are you so bitter, my dear? You’re like your grandmother. She died dissatisfied, and you’ve inherited this bitterness.” It was very sad to hear those words: they destroyed the idea of a happy ending after all the bitterness. If it’s true that this dissatisfaction is chronic, that means there will never be a big window in a beautiful house that I can sit in front of, drinking tea and looking at the green mountains in the distance, with a smile on my face.

Realizing that was sad, but also somehow liberating. I no longer saw self-love as a cumulative act: it no longer carried the burden of trying to dispel doubt and anxiety once and for all. I’ve started to be more accepting of this anxiety, for which there is no easy cure. I now know that I will be in my dark tunnel, which might take on a different shape, different contours, each time. But I also know that I deserve to be outside this tunnel, and the act of trying to emerge from the darkness is in itself an act of self-love, regardless of its nature and definition.

I’ve had to learn how to empty my attempts of specific goals, and not to fall into the trap of lists and expecting magical results from any specific act. I’ve had to learn that what worked yesterday might not work today, and to also accept non-doing as an attempt to console myself, as an act of self-love. To sleep 13 hours every day for a week and cancel dozens of invitations to go out, until I can muster enough energy to send an email.

Self-love while being utterly lost, when the worlds we knew have been destroyed and our support systems have collapsed, when the ground beneath our feet has turned into quicksand, is no easy task. Self-love, under these circumstances, is the hardest work. Striving, therefore, becomes the only possible act of self-love. Striving not to succumb to complete despair. To wake up every day, and try.

A few weeks ago, I cried and had a brief meltdown, then decided to go for a walk. I walked, crying, until I reached the ice-cream shop.

I sat in silence on a chair in the street, sullen, with messy hair and no bra, at 1.30 am, eating my ice-cream.

Then I took a taxi and went home. Sad, like I was before, and alone, except for the ice-cream. And I slept.

So here I am, striving. Tomorrow is just another day.

Comments

حبيته

تعليقي طويل حبتين وبالعامية.. مبارح عملت عفل لرابط المقالة وقلت خليا لبكرا.. اليوم أول مافقت فتحتا وقعدت اقراها وانا معتبرة انو هي محاولة لتغيير روتيني الصبح وحتكون متل كأني عم اقرا جريدة بقهوة مع قهوة الصبح.. واخر كلمة بالمقال كانت ليكني عم حاول.. متل ما انا حرفيا عم اعمل.. عم حاول اطلع من علب كآبتي.. صعب جدا.. بس ليكني عم حاول.

مرحبا-

حب النفس فعلا اشي كتير صعب وكتير بيحتاج قوة. بس هاد كمان مابيعني انو الي ماعم يقدرو يحبو نفسهم ضعفاء او جبناء....

مع كل أمنياتي بنجاح محاولتك :)3>

Add new comment