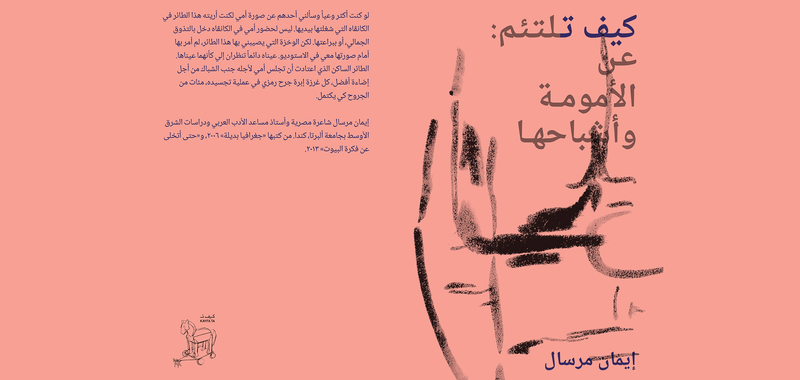

An exerpt from Iman Mersal's book "How to Mend: Motherhood and its Ghosts" published by Kayfa ta.

Introduction

When, in February 2017, my book “How to Mend: Motherhood and its Ghosts” was published, I imagined that my journey of writing on motherhood was, at least for now, completed. I seemed ready to part with it and move on to other projects. However, this has not happened in almost a year. I have never liked that cliché of “my books are my children,” but, funnily enough, I will use it now to explain my emotional attachment to this book: I have, indeed, placed my name on its cover confirming my motherhood of it, as absurd as it might be to think I could nurse it because I am a woman, or remember its conception, as that is an issue far more complex than I can remember in any detail.

My continuous concern with “How to Mend” after its publication had nothing to do with its specific topic, with the fact I had left things unsaid, or the growing number of reviews – although all of these were important reasons. What made me continue to write down my observations and diary on motherhood, as if in some never-ending project, was the accounts of others relating their personal experience of motherhood while addressing my little book in reviews or comments on “Goodreads” and social media, or in personal messages to me.

A critical definition of “productive reading” says that it is not limited to understanding and analysis, the reproduction of the read text, and that it neither stops at the enjoyment nor evaluation of the text. More than that, productive reading strives to produce its own text while grappling with what is being read. This was exactly what I needed to understand and celebrate until I could commit to other writing projects, irrespective of whether or not I still had questions about motherhood. What some readers of my book offered was real dialogue about a topic that is neglected in our Arab culture. What they also highlighted – an unexpected gift from digging around in their personal experience – was the importance of writing for understanding and communication.

I can say that my keen interest in motherhood goes back a long way and has always been linked to writing: from the first poem about my deceased mother that I read out in fifth grade at my school’s Mother’s Day celebration, over all the other poems in each poetry collection. But this interest needed encouragement, the right moment and maybe some strength on my part to be fulfilled. I began, in autumn 2014, to write about the absence of motherhood as personal experience in feminist literature, as a contribution to the second issue of the feminist magazine “Makhzin.” I put the research material on my office shelf. But then, gradually, I began to deviate from the safe path of my study, and I was surprised to find that I had other questions that arose from my own shaky experience as daughter and mother in comparison to the confident accounts of public discourse.

Luckily, at that time I received the invitation from Kayfa ta to contribute to their series. This was exactly the encouragement I needed to pose my questions in all consequence, without prior limitations to what must be said or how to say it. I remember that I initially described my project to Maha Maamoun and Ala Younis, the publishers of Kayfa ta, as "How to Be a Mother." And this vague title remained throughout the different drafts of the book, which only showed how much my various discussions with them at all stages of the writing process inspired me, as much as they gave me the necessary confidence to enter unsafe areas when necessary.

Writing is cause, process and result at the same time; it is an act of its own laws that help us discover, confront and perhaps reconcile with our personal scars. I am indebted to the act of writing itself; and although it can sometimes seem like a walk in the dark, it is also the compassionate hand that guides us inward on every journey.

Translated by Robin Moger

Editors Maha Maamoun and Ala Younis

On motherhood and violence

“You are not going to defeat me,” I say

“I won’t be an egg which you would crack

in a hurry for the world,

a footbridge that you would take on the way to your life.

I will defend myself.”1

The lines above are from a poem by Polish poet Anna Swir (1909–1983) in which she addresses her newborn daughter. But the poem was first published in the early seventies and so comes, in terms of the poet’s life, some thirty years after her own experience of childbirth. As readers it is difficult to avoid the question: Did Swir require all those years in order to nurture a rage of some kind towards her newborn daughter; to revisit or develop this rage in her poem, Maternity, in which the child’s arrival threatens the mother’s life and existence?

The profundity of what Swir grasped is not the generalization of the conflict between mother and child—it is not a conflict over ownership or gender or generation—but to link it with childbirth as a biological process in which one participant is a being that has lived, taken shape, and made certain choices concerning its existence before the moment of delivery, and another, smaller being: the doll that in that instant emerges into life out of the first.

This conflict between mother and child lies outside the grand narrative of human experience in which motherhood conventionally means giving, the melding of two distinct selves, a love unlimited and unconditional. It is as though Swir’s poem impels us to contemplate two motherhoods: the motherhood of the dominant narrative (constructed out of religious discourse, philosophies, morals, and received social values) in which motherhood is viewed as instinctual, innately immune to conflict and angst, and a motherhood of the margins whose narrative fragments may be found in medical books, literary texts, and records of domestic crime; that is, wherever voices attempt, through mental illness, in writing, or by criminal acts, to express the terror, conflict, and stress within their own experiences of motherhood.

I am not concerned here with how certain features of motherhood have taken root within the dominant narrative, but rather how we might listen to what lies outside this narrative and opposes it. How to see that a motherhood branded as purely altruistic and sacrificial might also harbor selfishness and profound feelings of guilt? How to understand it as an existential struggle, a tug-of-war between one self and another, and as an experience of connection and separation played out in many rites of passage, such as birth or weaning or death?

The ideal of motherhood in the dominant cultural narrative intensifies the guilt of those who doubt the existence of this ideal within their personal experience. It meets the expression of any divergent experience with moral and social condemnation, which may be why there are so few accounts of motherhood that lie outside the narrative. It may also be why Swir needed decades to free herself from what she was expected to say, something that in any case would have been impossible without those efforts to widen the scope of feminist inquiry into everything that generalizes and stereotypes the relationship of women with their bodies and the world.

The crack begins within

The mother refuses to be an egg that the newborn breaks en route to life. Herein the terror and gravity of the threat: the moment of a new person’s birth requires the death of another. The death of the old is an indispensable condition for the new to obtain space for its existence, as George Bataille has it.2 As though what Bataille sees as the enchantment in life’s tragedy is the very thing that Swir regards as a threat of erasure, the tragedy inherent in life’s most enchanted moment. In both instances, the crack of motherhood begins within.

A woman’s wish to be a mother is not entirely free from the egocentric desire to create an extension of her being, an image of herself

In his book The Selfish Gene Richard Dawkins describes the endless battles in which the gene must prevail if it is to preserve itself: survival, not of the fittest, but of the most selfish, the best able to triumph in its struggle for existence against the other genes. There is no such thing as sacrifice devoid of ulterior purpose. For Dawkins, selfishness is a means to preservation; investment in the gene is conditional on it proving that it has the ability to survive unsupported thereafter.3 The fetus takes half its genetic material from the mother and relies on her for everything it needs to exist, even if the provision of these needs goes against her own interests. Programmed for selfishness, the fetus’s approach is to subjugate the mother’s genes and make her act selflessly for its sake, through “love.” If we suppose that a woman’s wish to be a mother is not entirely free from the egocentric desire to create an extension of her being, an image of herself, to leave some trace that might live on after her death, then maternal feelings of love and selfless affection and sacrifice are themselves not innocent of the mother’s own self-love and selfishness.

By the same token, any medical description of the processes of pregnancy and parturition offers up numerous metaphors of threat, conflict, selection, investment, and risk. The womb defends itself against the harmful fetus: its walls thicken, which leads to bleeding. This is the means by which the mother’s body tests the viability of the fetus before permitting it to continue living. The mother’s body has to make sure that the pregnancy is a sound investment in the future. Should the fetus win the fight the placenta will form, but at the same time so too will a delicate membrane separating the blood of the mother from that of the fetus: fission, not fusion, is the condition for mutual survival.

The umbilical cord transports food and oxygen from mother to fetus and waste from fetus to mother, but in the transportation of everything that is necessary for the development of the fetus, disease can be transmitted from child to mother. Biologically speaking, the fetus is an alien body within the body of the mother, a parasitic creature, and its presence inside her has the potential to infect her with a number of diseases; it might also be the cause of her death before, during, or after birth.

We cannot expect this conflict, taking place on the biological level, to be wholly absent from the postpartum relationship between mother and child. It is the conflict that injects an ambiguous sense of threat into every sacrifice the mother makes for her child and a profound feeling of guilt into every act of self-love.

My son pointed at the huge statue, a crocodile and shark facing one another on a plinth, and asked,

“If the crocodile fought the shark which would win?”

“I don’t know, what do you think?”

“The dinosaur, of course!”

Guilt

If there were a fight between the mother’s self and that of her child then neither would win. It is, “of course,” the dinosaur that wins, and its name is guilt.

Guilt seems to be the emotion that unites all mothers, whatever their differences.4 Guilt inhabits the gulf between dream and reality, as it does in the relationship between child and parent, in love and work and friendship; it is also generated in the gap between the ideal of motherhood in the dominant narrative and the failures that attend it in daily life. So central an emotion, in fact, that it serves as a viable definition for a mother’s quotidian experience: your son’s weight is below average for his age; you can’t be feeding him enough. He woke terrified from a nightmare because he doesn’t feel safe. You didn’t hug him at the school gate because you were late for work. You never learned how to skate though you will take him to the ice rink, queue in temperatures several degrees south of zero, and can offer no assistance when it comes to wrestling on the extraordinary boots, and in the end he will go off to skate alone while you wait in the café reading a book. You are moody in the morning, distracted in the evening. Other mothers enjoy playing chess and have memorized numberless children’s rhymes.

The mother who feels no guilt towards her children is a woman whom an angel visited as she gave birth, splitting opening her heart and extracting the black speck that is the root of all evil, liberating her from her former identity and cleansing her of nihilism and ambition alike, as was done to the prophets to equip them for their divinely appointed task.

Guilt is not just associated with feelings of inadequacy, nor with the plight of the modern woman torn between work and her maternal obligations; at times it springs from an ideal model of motherhood in which there is no limit to the love and protection and time and education and so on that a mother can give her child. It may also come from that part of her personal history that predates her motherhood.

No sooner sure of the pregnancy that I had longed for with all my being than I realized I felt none of the joy that I’d anticipated. I was overwhelmed by a deluge of anxieties, fear that my body wasn’t fit for purpose. I was thirty-two and suddenly I was aware that I’d never paid the slightest attention to my health, my body a vessel for whatever it was I thought of as my self: a machine that never asked for anything but was nevertheless expected to keep on serving me. Ten years before I’d begun smoking insatiably and had lived a more-or-less bohemian existence in which the body required neither regular meals nor sleep. All this, in addition to a history of antidepressants, sleeping pills, sedatives, plus anything else I could lay my hands on.

This was the history of my body before pregnancy. But no sooner was it upon me than there materialized various institutions and organizations working day and night to enlighten me about every possible risk this history of mine might pose to the fetus. Guilt was the first emotion I felt towards my motherhood.

One day, in the third month of my pregnancy, I called my father. I asked him if I’d contracted German measles as a child. “You didn’t have measles, if that’s what you mean,” he said. “What’s German measles?” To tell the truth I had no idea whether or not we were talking about two different kinds of measles. The night before, I’d read about the increased risks associated with mothers who’d contracted German measles, and how the virus could be transmitted to the fetus leading to a child born dumb or blind or with a defective heart or nervous system.

It never occurred to me that I would find myself debating medical terminology with my father. I asked him if I could get hold of a medical report from the clinic where I’d been given all my injections as a child, to which he said simply that the clinic we’d used up until the late ’70s had been demolished, and that he’d watched with his own eyes all the files being incinerated before the practice was relocated to a new building.

For and against institutions

Maybe I thought it would have been kinder not to have read up on German measles, that such detailed knowledge was the gateway to fears and troubled sleep now the only institution able to put my mind at rest had disappeared from the face of the earth. A body with no documented medical history confronts the revolutionary advances of modern medicine with its constant questioning, plotting the body’s future from a catalogue of past illness and inoculation.

The modern woman is denied the gift of calm, besieged as she is by knowledge of what will happen to her pregnant body day by day. The doctor, leaflets from the clinic, self-help books that tell her what to eat and how she must feel and the average weight gains she’ll experience at every stage, medical reports detailing bouts of nausea and bizarre dreams in the first months or the back pain and an increasingly frequent need to urinate that attends the end. And over and above it all, the mountain of medical tomes and specialist websites warning of the disasters that she and the creature in her womb might encounter, from miscarriage to premature birth, from eclampsia to fetal deformity, from chicken pox to the possibility of delivering a disabled, disfigured, or genetically defective baby.

Do the institutions of modern medicine stand between a mother and her fetus? Is the lesson here that an awareness of the risks of pregnancy causes considerable stress, and not a sense of security, which might be better achieved by ignorance? There has been some important writing critiquing the role of medical institutions in the West, and those that deal with childhood and motherhood,5 but the truth is I myself am unable to adopt the same attitude without confessing that in my case such a stance would lack integrity. According to the World Health Organization over three hundred thousand women lose their lives every year due to complications arising from pregnancy and childbirth, and 99 percent of them die in what is termed the Third World.6

I experienced pregnancy and childbirth in the “First World” and enjoyed the benefits of the latest advances in medical science, but I belong to the Third. My attitudes towards these institutions are problematic and informed by my experiences in both worlds. As a child I knew women who died in childbirth. I could tell many tales. But do we have to go to that extreme? It’s enough to say that my own mother died aged twenty-seven after several hours laboring to deliver a stillborn boy. That she never had the books to tell her that a fetus which remains motionless for several days in the seventh month of pregnancy is a sign of danger, or that the hospital she went to was unable to save her.

My mother, who died in the seventies, is just one of many similar women from the Third World, women who are unfortunate enough to go through childbirth just as modernity is disrupting traditional medicine and the oral transmission of experience and expertise, even as they lack the medical institutions capable of playing this role due to the failures of this same modernization.

I gave birth to my eldest boy in Canada, far from family and more or less on my own, since I had arrived only months before and had yet to make any friends. Nonetheless, I received comprehensive care from the country’s medical institutions. During one routine check-up my doctor gravely informed me that she believed I might have post-partum depression. She gave me a booklet about the condition and sent me off to attend group therapy sessions: five other mothers—“patients”—each dealing with different problems. For six months we met once a week with a psychiatrist and social worker. At each session we were required to carry out a specific exercise known as “the task.” For instance: to talk about our most terrifying experience from the previous week, about any desires we might have had to harm ourselves or the child, about dreams and nightmares, about the number of times we burst into tears out of the blue. They were all Canadians, born and raised in Edmonton, and all had family support in some form or other, all except myself and an Iranian doctor who had yet to obtain a license to practice medicine in Canada.

One loathed her mother, or so she said: “I hate my mom, I despise her more than anyone else on earth. Just to think that my relationship with my little girl might turn out like my mom’s and mine leaves me dead with fear.” One had insomnia: she’d watch over her baby boy as he slept, so she could wake him if he suddenly stopped breathing. The Iranian doctor told us that she’d delivered her son by natural birth in hospital and that everything had gone smoothly. Only, she’d been unable to breastfeed him for a whole week thereafter: “The milk dried up in my breasts. My boy’s got a genetic deformity in his lower lip which prevents him from latching on and sucking. The doctors tried everything but I couldn’t do it. I called my grandmother in Isfahan and told her what had happened. ‘Get a tight-toothed comb,’ she said: ‘Put it in warm water and when it’s dry stroke your breasts with it every couple of hours.’ She also said, ‘Hold the boy under your arm with his feet sticking out behind you and supporting his head with your hand, as though you’re dancing with him, and he’ll feed.’ In under a day I was breastfeeding him.”

We were all most impressed with the brilliance of this traditional advice and its success, but the Iranian doctor came across as utterly wretched. To me, it felt as though she was incapable of enjoying the experience because her motherhood wasn’t taking place at home, or that her joy had been put on hold till she could return. I realized that, regardless of the efficacy of the group therapy or the institution which ran it, she and I could not feel secure because we had entered into this experience while we were far away from our families; because, in our exile, there was a frame of reference that we lacked.

References for motherhood

Thinking about motherhood seems to require looking in two different directions simultaneously: to the past, when I was daughter to a mother, and to the future, where I became a mother to my son. I do not know in what way motherhood is shaped by our childhoods but I can appreciate that it cannot be sidelined or ignored. Might childhood itself be an unseen cause of the angst of motherhood?

If your mother was excessively tender and caring then you might want to be like her, and you might feel guilty because you can’t. If your childhood saw your mother invest everything she had to make you turn out out as she wanted, then you might repeat the same process with your child, or, having known what it is like to suffer in the process of casting off the weight of your mother’s ambitions, you might consciously restrain yourself.

There must be some frame of reference that shapes the motherhood of which you dream

Whether your mother was serene or tempestuous, warm or cold, rational or crazy, there must be some frame of reference that shapes the motherhood of which you dream. Though what if your mother died before you could form a memory of your relationship with her? What if a mother’s absence or disappearance is the point of reference you turn to or fight against when you become a mother? And what of the experience of motherhood away from home, when you yourself are absent from your “motherland”? Does this make you freer when playing the role of mother, or does it leave you more lost than ever?

Eve might be the only woman who went through motherhood with no personal or collective memory of being a daughter, without any prior experience to light her way. How then did Eve deliver her firstborn? How did she deal with the nausea during the first months of pregnancy? Did she love her boy when he came out of her? And who was it cut the cord that ran between them and what implement did they use? Were there other mammals for her to observe and imitate or does this kind of knowledge derive from instinct? Did Eve want to be a mother or not? How could she even tell if she had not come from a mother’s womb herself and there had never been another woman in the world before her?

We are told that Eve and Adam committed a grave sin and were expelled from Eden. Adam was condemned to till the earth, a punishment that we, from our vantage point in the modern world, might say is not confined to man alone but extends to all mankind, men and women alike. But Eve’s punishment was hers and hers alone, one that no man might share: the pangs of childbirth. “Unto the woman he said, I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in pain thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee” (Genesis, 3:16).

It is difficult to picture the first birth on earth: no precedents and no institutions. It is difficult to imagine those women who give birth in deserts and fields, in kitchens kneading dough or on the outskirts of cities, who lost their lives before the invention of anesthetic or antibiotics. But that said, it is still difficult, even now, to give birth and to be a mother with every possible social and medical privilege at your disposal. For all the doctors, nurses, spousal support, medicines, and painkillers, childbirth is a solitary act. You must give birth alone, must rid yourself of what’s inside you because the pain is insupportable, because the newborn’s life is conditional on separation, the same separation on which your existence now depends.

Postpartum, a journey begins in company with a creature that is supposed to be a part of you but that might seem to you at times to be a stranger. With every step on this journey a new question will present itself, as though your duty is to invent motherhood wholesale, as though it never happened to anyone before you, as though it is an endless test of your own existence, of your relationship first with your body, then with everything you once assumed was you.

Feminisms

If you imagined that modern feminism would pay close attention to your personal experience you might find yourself disappointed. Many feminist movements go to war for women’s rights, for equality in the workplace, before the law and in the public sphere. You will find most of them radical in defense of your right to draw a salary during maternity leave, to reduce your working hours while breastfeeding, to oppose the state’s attempt to cut costs when it comes to funding childcare or by reducing health insurance coverage for women with postpartum depression.

Feminist activism can give a voice to issues that remain unvoiced, like the rights of single mothers or gay mothers, but in all these victories a generalized picture of women pertains, an insistence on their objectivity as a group and as a social force: men’s peers.

One of the crises of Western feminism derives from its idea that to speak of the special nature of motherhood detracts from the coherence of calls for gender equality. This may be the reason it avoids listening to individual experiences and why, when it does listen, it criticizes them for creating a separation between motherhood and society (and its institutions), or for turning women into no more than bearers of and carers for children, or ultimately for failing to narrate a subjective experience that supports a particular feminist discourse.7

In the majority of these discourses, which I see sitting on my shelf from where I write, motherhood seems like a self-contained experience sealed away within the borders of the community of women as it battles against patriarchy; there is no attempt to look deeper into this “different” experience with its potential to alter the consciousness of men and women alike.

Until feminist theories take account of the violence, rage, and frustration inherent in motherhood, you will have to narrate your own experience or learn to take refuge in a narrative that will help you see that you are not alone.

Fear of parting

The relationship between Syrian poet Saniya Saleh and her two daughters Sham and Sulafah occupies a central place in her work, her last two collections in particular. There is a fundamental theme that Saleh returns to whenever her daughters appear in a poem, which I might describe as a fear of parting. She writes:

Sink your head in me,

pierce me through almost

till our bones vanish one into another

and we are most contiguous,

enmeshed: one, double-hearted.

Touch me, as God touched clay,

and I rise, human.8

There is no anger or violence in Saleh’s motherhood; there is a mother fearful of separation, of her daughter being swept far away. She is asking her daughter to enter into her, to disappear inside her: to enact the reverse of childbirth and return to the womb once more.

Even if Saleh herself did not need this separation, she surely knew how vital it was for her daughter, the first step towards knowing herself, discovering “the other” to which the mother belongs, and touching for the first time what we might term “identity.”

Saleh’s fear of parting from her child stems from more than an instinctive predisposition for giving and sacrifice. It is, as well, fear of a malevolent world, as though motherhood were a womb giving protection from terrors that the mother has experienced and the girl is destined to go through the instant they part.

Pearl,

you slept inside me for whole ages,

listened to guts clamor,

roar of blood.

So long I hid you, for so long

until history might end its sorrow

until the great warriors end their wars

and the men in hoods flay their last victim,

until an age of light comes in

and one of us comes out from the other.9

This excerpt is from a poem entitled “Sham, Set Night Free.” Sham is not just the name of the poet’s daughter; it is also a word that means Syria, her homeland. The title’s symbolism, its conflation of daughter and country, is impossible to miss, as is its resistance to the trope of mother-as-motherland in modern Arabic poetry.

Comparing Swir’s and Saleh’s poems we see that to Swir childbirth is a fundamentally important and interior moment of violence, whereas with Saleh violence is an exterior phenomenon which stems from history, from its warriors and executioners. In the line, one of us comes out from the other, it is as though Saleh is negotiating on two fronts simultaneously, public and private: birth is a shared act in which the mother is born as her baby is born. Saleh’s interest in her identity is no less intense than Swir’s, but she is unable to sidestep a cultural context burdened by frames of reference: on one side the sacred status of motherhood in Arab culture and on the other modern Arabic poetry’s grappling with the violence of an external reality.

However, a wider-reaching reading of Saleh’s poems reveals another moment behind her fear of parting from her daughter: an older fear; of parting from her mother. In one of her early poems she writes:

Weep hard, mother,

at the top of your voice.

There is no void but our throats

so where is the great wind which carries the voice in pain?

Return to me, then,

early and naïve childhood,

great plain broader than imagination.10

The poet fears her old and intimately familiar estrangement, harking back to her own separation from her mother. She puts off her separation from her daughters even though she knows it is bound to happen. She seeks to protect her identity as a mother for as long as possible having lost her identity as daughter with her own mother’s death. For her, motherhood is a womb which protects not only from the evils of the outside world but also from our personal experiences with our mothers.

My son was four when he asked me: “What was that place we went yesterday?” I tried to remember and when I realized that the only places we’d been in the last few days were the nursery and the park I thought back to the previous week: “We went to the doctor, Youssef.” He looked at me impatiently: “No! Yesterday!” I told myself that this was a misunderstanding, not about place but about time; to Youssef, say, yesterday might be last month. All my attempts to come up with an answer came to nothing, but making an effort I realized that, quite simply, I had been with him in a dream. That when he dreamt and I was with him in the dream then I was really with him, and it was only natural that I should remember what had happened to us there.

Taking refuge in the narrative

In J. M. Coetzee’s novel Elizabeth Costello, John, son of the famous writer Elizabeth Costello, only abandons his refusal to read his mother’s work when he is thirty-three years old. That was his reply to her, his revenge on her for locking him out. She denied him, therefore he denied her. Or perhaps he refused to read her in order to protect himself.11 How had Costello rejected her two children and why?

The narrative offers us scattered fragments of Costello’s performance as a mother. We read that, as far back as he can remember, his mother has secluded herself in the mornings to do her writing. No intrusions under any circumstances. He used to think of himself as a misfortunate child, lonely and unloved.12

We only see Costello’s motherhood through her son’s eyes. She never addresses it during the course of the book; she speaks only about her writing and certain grand subjects: realism, Kafka, the treatment of animals.

We can imagine a young mother struggling to divide her day between work and her two children, sometimes guilty because she isn’t spending enough time with them. We can imagine this mother, moody in the morning, lacking sufficient energy to deal with the world, locking the door in her son’s face. But Costello seems more complex than this. John himself wonders who she really is, something he does not know himself and which, deep down, he does not wish to know.

Were he to speak, he would say: This woman, whose words you hang on as if she were the sibyl, is the same woman who, forty years ago, hid day after day in her bedsitter in Hampstead, crying to herself, crawling out in the evenings into the foggy streets to buy the fish and chips on which she lived, falling asleep in her clothes. She is the same woman who later stormed round the house in Melbourne, hair flying in all directions, screaming at her children, ‘You are killing me! You are tearing the flesh from my body!’13

Unlike Elizabeth Costello, Adrienne Rich was no fictional character, but she was a writer and a mother. In May 1970 Rich wrote in her diary: To suffer with and for and against a child—maternally, egotistically, neurotically, sometimes with a sense of helplessness, sometimes with the illusion of learning wisdom—but always, everywhere, in body and in soul, with that child—because that child is a piece of oneself.14

To be a writer and a mother is not inherently contradictory

We can imagine that at certain moments, in certain ways, Rich is like Costello, for although her child is a piece of her there comes a moment in which she feels helpless, unable to escape her identity as a woman with her own personal project predating motherhood; that her identity took shape through writing just as the identities of others are formed by what they hope to contribute to the world.

To be a writer and a mother is not inherently contradictory, but here and there throughout her writing Rich speaks of her frustration at being unable to find time for herself, of bouts of anger and tears, of her son, who refuses to let her be an “other” and will drop whatever he’s doing, leaping on the typewriter as soon as she sits down to work. I believe that she sometimes wished her child, this piece of her, might separate from her for a while, might be able to understand that she had the right to go off alone to encounter herself.

Like Costello, Rich confronted the juxtaposition of her identities as writer and mother: Once in a while someone used to ask me, ‘Don’t you ever write poems about your children?’ The male poets of my generation did write poems about their children—especially their daughters. For me, poetry was where I lived as no one’s mother, where I existed as myself.15

It is not just a juxtaposition between two elements with the mother-writer/writer-mother identity, it is a rending, a struggle over time and energy. When the writer manages to be a mother for a day she will feel like a failure for all the reading or writing she did not get done. When she has a day to herself she will be tormented by her selfishness. When, on another day, she’s able to write with her boy perched on her knees and play hide-and-seek as she ponders changing a word in a poem there is no guarantee that she won’t in any case feel guilt or failure. No guarantee, moreover, that her child will one day read what she has written or that he won’t be angry, like Elizabeth Costello’s son.

Giving birth, remember that you are not an egg. Swir knew that. For days or hours you may feel you’re at the mercy of a womb surrounded by organs, but this womb is surrounded, too, by an existence and a history that predates the pregnancy. True, childbirth is the moment that will split you in two but is there not some breakage in all our lives; a crack, as Scott Fitzgerald has it?16 Isn’t this crack itself the identity by which we move through the world?

Birth is a threshold to a journey, the transition the body makes in order to become self-aware. Rich targets it for this reason: I had been trying to give birth to myself; and in some grim, dim way I was determined to use even pregnancy and parturition in that process.17

It is as though the two poets, Anna Swir and Adrienne Rich, each wanted to say in her own way: “I am aware of my fracture. I have lived with it from before childbirth. I am fragile, and giving this doll life then having it separating from me is a fresh crack in my consciousness. It is not enough that I have just given birth to this doll, I must now give birth to myself for its sake, a self-birth that will either deepen these cracks within me or help them mend.”

By way of Conclusion:

Mourad18

I don’t want to die, Mama.

Habibi, you’re not going to die, you’re only four years old.

I don’t want to get old then die, Mama.

Habibi, maybe you’ll be ready by then.

But why do we die, Mama?

Habibi, maybe it’s because we … I mean … Maybe because we’re greater than life.

Mama, tell God that Mourad doesn’t want to die.

But habibi, I’m not in touch with him.

- 1Anna Swirszczynska, Talking to My Body (Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 1996).

- 2Georges Bataille, Literature and Evil (London: Calder and Boyars, 1973), 11.

- 3Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989). In his book Dawkins treats the mother as a machine that does everything in its power to ensure its genes live on in others (106). Elsewhere he addresses the selfishness of the child who regards his life, no matter how much the mother sacrifices for its sake, as more valuable than hers because in the end only half his genes come from her (131).

- 4There are a number of studies and surveys that confirm the centrality of guilt to modern motherhood, for example: Susan J. Douglas and Meredith W. Michaels, The Mommy Myth: The Idealization of Motherhood and How It Has Undermined All Women (London: Free Press, 2005); and Sheila S. Coleman, Mommy Grace: Erasing Your Mommy Guilt (New York: Faith Words, 2009).

- 5See Adrienne Rich, Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1997); and Sara Ruddock, Maternal Thinking: Towards a Politics of Peace (Boston: Beacon Press, 1989).

- 6World Health Organization, UNICEF, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, and World Bank, Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division, 2015, http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/maternal-mortality-2015/en/, 16.

- 7See Patrice DiQuinzio’s criticisms of all attempts at building theory on the basis of personal experience. DiQuinzio understands the importance of personal experience but insists on its contradictions and failure as in Adrienne Rich’s and Sara Ruddock’s experiences of motherhood (cf. Of Woman Born and Maternal Thinking). See Patrice DiQuinzio, The Impossibility of Motherhood: Feminism, Individualism and T the Problem of Mothering (New York: Routledge, 1999), 205–20.

- 8Saniya Saleh, The Complete Poems (Damascus: Dar Al Mada, 2008), 282. In another poem dedicated to her daughter, Saleh writes: My little one / carry me tucked under like the flesh of your arm / I won’t be able to part (298).

- 9Ibid., 134–35.

- 10Ibid., 106. Saleh also pleads with her mother to return because she is her childhood and lost paradise, pleas that are punctuated with tears and terror: An old pigeon addressed as Mother / I am her eternal terror / I am her undrying tears (126).

- 11J. M. Coetzee, Elizabeth Costello (New York: Viking Press, 2003), 5.

- 12Ibid., 4.

- 13Ibid., 30.

- 14Rich, Of Woman Born, 22.

- 15Ibid., 31.

- 16F. S. Fitzgerald, The Bodley Head Scott Fitzgerald: This Side of Paradise: The Crack-up & Other Autobiographical Pieces (London: Bodley Head, 1965), 273–78.

- 17Rich, Of Woman Born, 29.

- 18Iman Mersal, Alternative Geography (Cairo: Sharqiyat, 2006).

Add new comment