“Even the streets of your country have turned out to be harsh," those were Ahlam's precise words, the woman whose speech inspired the concept behind my article. As I journeyed home, her words reverberated in my mind while casting a contemplative gaze out of the car window towards the Corniche Road and its endless disruptions. Her sentiments stirred a question within me about the extent to which women experience estrangement and alienation, and how this impacts their daily lives, work, and mobility within the city. This daily routine oscillates between the harshness of fast-paced movement and the chaos of aspirations amidst the crowded confines of capitalist cities and their public economic, political, and cultural arenas. Particularly notable is the absence of feminist urbanism from urban planning, which fails to delineate the form of public spaces surrounding them. This concept aims to challenge the supposed neutrality of urban planning, exposing the inherent biases by examining women's experiences in everyday life. It holds the promise of yielding measurable results and conclusions through the lens of urban studies. I firmly believe that cities are more than just grand luxurious buildings and silent roads; they are living testimonies to the tales of their inhabitants, as Shakespeare1 acknowledged when he pondered, “What is the city but the people?"

The spatial marginalization of women in urban settings.

"Ahlam,2" an Egyptian woman in her mid-thirties, is one among millions whose lives are shaped by the patriarchal capitalist structure. Hailing from one of the villages in the Egyptian Delta, she migrated to the city years ago in pursuit of her dreams, buoyed by clichéd slogans like "Follow your passion blindly" and “Your hard work ensures your goal is reachable”. Consequently, she involuntarily refers to the city as “your country" in her speech, expressing her profound sense of estrangement from urban environments that have repeatedly let her down. Ahlam begins her story by stating, "Throughout my life, I have harbored a fear of walking in the streets. The city's alleyways are dimly lit, dusty, and their unpaved or poorly maintained surfaces become treacherous when it rains. Yet, it’s a situation we feel entirely powerless to rectify."

“Ahlam” completed her elementary education while residing in a house far from what philosopher “Alain de Botton” refers to as "The Architecture of Happiness". Its dilapidated walls are situated within a poor village that has been overlooked by urban development initiatives. This village is tethered to the outside world by a single main road, which is in no better condition than its cramped alleys and lacks safe public transportation aside from a bus that transports students twice daily, while residents rely on tuk-tuks3. Due to safety concerns, Ahlam's family restricted her outings, confining her within the village's boundaries. When she enrolled at the university in Cairo, she anticipated that her path to a fulfilling life would finally be paved, as big cities often serve as a refuge for marginalized villagers with aspirations for a brighter future. However, she was met with disappointment.

With a heavy heart, Ahlam recounted, "My excitement quickly dissipated on my first day at university when I was confronted with the bustling streets of Egypt4: towering buildings, expansive squares, congested roads, speeding cars weaving through traffic, and sidewalks occupied by cafes and shops. Overwhelmed, I took a step back. It was at that moment that I As if I backed along my fears into my suitcase and brought them with me to the city."

Ahlam recounts her journey: "I got married during my second year of university and relocated once again, this time to Alexandria. I resided in Al Amriya “settlement5”, a distant area from downtown, where navigating through dimly lit alleys became a nightly challenge. Venturing outside became even more daunting after becoming pregnant and giving birth. Childcare facilities were either far away or unaffordable, leaving me unsure of how to manage outings with my infant. Consequently, completing my university degree became unattainable, and without it, securing a decent job seemed impossible. I felt like a stuffed hungry someone man6, yearning to immerse myself in the company of others, yet unable to do so. I experienced the estrangement described by Muhammad Mounir: 'My only companion is my alienation, always lingering around me7.'"

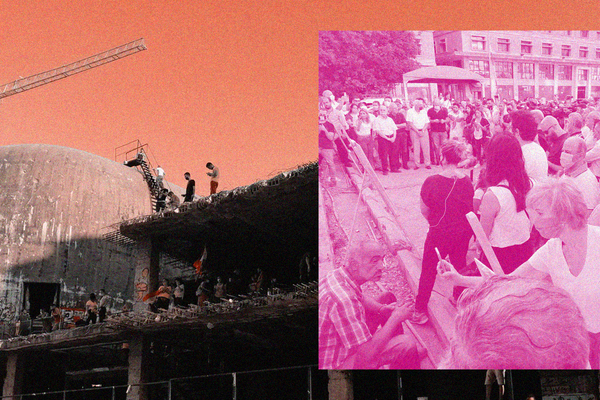

Indeed, Ahlam is not alone in experiencing the sense of isolation. She is one of those who Cities have often failed to embrace or acknowledge their aspirations. Egyptian novelist Tariq Imam captured Ahlam's plight, along with that of her sisters and others like her, in his novel "Cairo's Maquette"8 which was shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2022. The novel delves into urban planning and its impact on residents' lives. Imam portrays one of his characters, who migrated from a village to Cairo, as feeling trapped between two cities, akin to being stuck on a scaffold: "Unable to face the sun or look down at the ground, as either action would lead to a fall." This metaphor reflects the psychological anguish experienced by individuals in cities where they have endured hardship, hindering their ability to engage fully. However, this predicament is particularly acute among women, who feel marginalized and invisible. Their voices go unheard, and their desire for peaceful and dignified existence remains unfulfilled, as articulated by Naguib Mahfouz in his masterpiece "Children of Our Neighborhood9": "The neighborhood belongs to everyone, and women constitute its distinguished other half. It is disheartening that our neighborhood fails to respect women, but true respect will come when justice and compassion prevail."

Women encounter unfriendliness in capitalist cities.

I directed my inquiry to architect “Aya Mounir”, the founder of the "SuperWomen" initiative dedicated to addressing women's issues in Egyptian society. During our conversation, she explained that cities are primarily designed to accommodate cars, often at the expense of the population. She further elaborated on the findings of a previous study 10conducted by the University of Pennsylvania, which highlighted the exacerbation of women's reliance on cars due to the proliferation of highways. Additionally, Mounir referenced the perspectives of J. H. Crawford, author of two books on car-free cities, who emphasized the detrimental impact of cars on society, including the degradation of public spaces and the reduction of social interactions. Mounir furtherly stated: "While men enjoy the luxury of freedom of navigating the city, it remains challenging for them to carry out tasks and run errands without a car. For instance, even a simple trip to the supermarket entails long walks and navigating hazardous highways, not to mention the financial burden of unreliable public transportation. Now, consider the plight of impoverished women in this scenario. These women not only lack the luxury of car ownership but also face obstacles to walking freely and safely on well-lit and paved roads, as they are often subjected to harassment. This exacerbates their fears while moving around the city alone or using public transportation, especially in isolated areas or late at night. Unfortunately, this situation persists due to the city's urban planning neglecting the safety needs of women. There are insufficient measures in place to address harassment, such as the absence of security booths, surveillance cameras, and adequate lighting at public transportation stations. Furthermore, these stations lack shelters to shield commuters from the scorching summer heat and winter rain."

Mounir also emphasized the significant connection between the urban planning of Egyptian cities and the economic empowerment of women, which currently fails to achieve gender equality and often results in women being deprived of fair access to economic resources due to the significant urban disparities prevalent today. She elaborates: "The challenge of safely and conveniently commuting to workplaces located far from women's residences is a major obstacle to women's full participation in the labor market. This difficulty arises from the challenges women face when navigating the city for work, shopping, or taking their children to and from school, particularly in areas distant from their homes." Consequently, they struggle to meet family needs or strike a balance between family responsibilities and job requirements. Furthermore, they lack the opportunity to find suitable, affordable housing near their workplaces.

As a result, many women decline job offers, and employers, for similar reasons, often opt not to hire them. Consequently, Egypt faces a complex situation: cities lacking women-friendly environments, unsafe streets and transportation options, and limited job prospects. This issue is compounded by the spatial separation of commercial and residential areas, with commercial zones predominantly located in the city center and residential areas situated on the outskirts. This spatial divide exacerbates the urban gap between the affluent and the impoverished.

In fact, non-residential commercial real estate comprises 61% of the market value of Egypt's real estate sector, as reported by the MarketLine Foundation for Economic Research in December 2019. Meanwhile, housing prices have surged amidst accelerating inflation rates, reaching unprecedented levels, even as the availability of vacant apartments dwindles.

Representation of women in the capitalist city economy

By the same intimation, architectural researcher Reem Sharif argued, through a series of articles published in the "Urban Observatory," a project under the "Ten Toba" Foundation focusing on urbanization issues, the persistent neglect of gender considerations in urban planning practices. In her work titled "Housing Conditions in Egypt 2022," Sharif emphasized that the city fails to meet women's needs or prioritize their safety concerns when navigating crowded streets or utilizing public transportation. Instead, these activities often evoke feelings of fear and remind women of past traumas and experiences of violence in public spaces. As a result, women's proportional representation in the city's economy is impacted, leading to their spatial alienation translating into economic marginalization.

Egypt placed 134th out of 146 countries in the "Gender Gap for 2023" report by the World Economic Forum. A previous study titled "Work Obstacles Facing Women in Egypt," published in 2020, highlighted that challenges in mobility within cities hinder women's engagement in the labor market. Additionally, World Bank research indicates that aligning women's participation in the labor force with men's could boost the gross domestic product by 34%.

However, despite Egypt's per capita GDP reaching approximately $3,698 in 2021 according to the World Bank, society does not fully benefit from its investments in human capital. This may partly explain why Egyptian cities are slipping in global quality of life rankings. For instance, Cairo ranked 226th in Mercer’s quality of living classification for the current year, 202311.

Architect Nermin Baligh, the founder of Archimaker, the first virtual engineering office in the Middle East, emphasizes that architecture aims to promote human well-being, irrespective of identity, gender, or health and social conditions. While acknowledging the need for particular consideration for women in urban planning standards, Baligh underscores that facilitating human interaction within society is the overarching goal of architectural art. However, she notes that current Egyptian city planning lacks this aspect in its design and layout. Nevertheless, there is a noticeable shift towards adherence to recognized architectural standards in the design of new Egyptian cities. This includes measures such as facilitating traffic flow, providing wider spaces for safe pedestrian movement, ensuring sidewalks with suitable heights, and incorporating ramps for strollers and wheelchairs. Notably, these features are prominently integrated into shopping center designs, which also include amenities for nursing mothers, all aimed at promoting the well-being of all members of society.”

Why do capitalist cities antagonize women?

Cities worldwide are regarded as prime destinations for young individuals owing to their perceived capacity to enhance their abilities in facing future challenges; with 55% of the global population residing in those cities. This figure is anticipated to escalate to 68% by 2050, as per United Nations projections, aligning with economist Edward Glaeser's concept of the "Triumph of the City." This phenomenon is linked to the widespread emergence of human innovations and the expansion of intellectual capital during the industrial revolution, driven by major cities operating within a global economic system that relies on exploitation, particularly associated with the rapid growth of urban spaces and public areas. This growth undermines the process of social reproduction traditionally associated with families12, particularly women, in favor of amassing wealth for the affluent elite through the coercive transformation of public spaces into profit-driven ventures benefiting capitalist real estate developers."

In his book "Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to Urban Revolution," David Harvey, the social and geographical theorist, characterized the pervious prospect as the process of "accumulation by dispossession." He characterized it as the process of "accumulation by dispossession," a manner that positioned the neoliberal city as the epicenter of revolutionary movements, rather than the factory, as emphasized by the renowned philosopher and economist Karl Marx in his seminal work "Capital." Through embracing this perspective, we can expand our comprehension of class conflict within existing capitalist cities, which rely on spatial alienation, urban segregation policies, and the exploitation of public spaces.

In fact, the neoliberal age has evolved into an appropriation of deeper human necessities, such as environmental justice and adequate housing, alongside the disparities in the right to the city, articulated by the French philosopher and sociologist “Henri Lefebvre” in his work "Le Droit à la ville." This was published two months before the eruption of the student uprising in France in May 1968. “Lefebvre” illustrates in his writing the urban dilemma of exploited industrial capitalism, the impact of urban acceleration, and spatial disparities between affluent and impoverished neighborhoods regarding access to public services, which fosters social tensions, engendering class conflicts and an escalating sense of spatial estrangement, animosity, and resentment among residents within the same society13.

In addition to advocating for the right to the city, the eleventh goal of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals aims to create cities that are inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable, catering to the needs of their residents. Achieving this requires a greater focus on improving urban environments. Feminist urbanism places women's experiences at the forefront of urban planning efforts, recognizing that, historically, cities have not been built with gender neutrality in mind. Planners and architects have often failed to acknowledge the complex and unequal gender dynamics, resulting in designs that prioritize costliness, large-scale construction, and highways that disrupt residential areas in favor of commercial and industrial zones.

This perspective was strongly advocated by the American writer “Jane Jacobs” in the mid-twentieth century. She vehemently opposed urban development plans that she believed were detrimental to cities, advocating instead for the preservation of existing public spaces that foster social interaction rather than serving purely capitalist interests. Jacobs' activism brought her into conflict with real estate developers, particularly after successfully halting a project to build a highway in Manhattan that would have divided Washington Square Park. In her influential 1961 book, "The Death and Life of Great American Cities," Jacobs argued that costly urban planning decisions and encroachments on sidewalks and parks not only disrupt community dynamics but also erode the natural essence of urban life.

Returning to the tale of "Ahlam, and me listening to her while heartfelt words penned by the late writer “Hanan Kamal” in her book "Green Notebook and Letters, lingered in my mind: "Next time, I will ask God to create me in a beautiful city, for my soul has dried up from this surrounding ugliness." As “Ahlam” concluded her narrative, she lightened the mood with a jest, "Perhaps I'll have better luck leaving in the metaverse," alluding to the concept of existence within virtual realms. Then, turning the conversation towards me, she inquired, "Why don’t you share with me how the streets of your own city have treated you?" I smiled wistfully as my thoughts drifted away…

Translated by Rola Adel Rashwan.

- 1William Shakespeare, "Coriolanus Tragedy", translated by Gibran Ibrahim Gibran, Arab Foundation for Studies and Publishing Edition, 1981, Chapter Three, Scene One, Page 122.

- 2A pseudonym to preserve her privacy.

- 3A three wheeled motorcycle used as an affordable means of transportation, a “rickshaw” that is Locally named as "tuk-tuk" in most parts of Egypt.

- 4Among marginalized villagers, the city of Cairo holds a distinctive association with the name "Egypt" compared to other cities in Egypt.

- 5Situated in the Al-Amriya district in the western part of Alexandria Governorate, it acquired its name due to its proximity to the leper isolation zone.

- 6An Egyptian popular saying indicating a state of not engaging in a particular action.

- 7An excerpt from the song "Younis", lyrics by Abdul Rahman Al-Abnoudi, from the album "Ta'am Al-Buyut", 2008.

- 8Tarek Imam, "Cairo Maquette", Al-mutawasit Publications, 2021, electronic version on Abjad application.

- 9Naguib Mahfouz, "Children of Our Alley", Egyptian Diwan Publications, 2022, electronic version on Abjad application.

- 10Carol Sangor, “Girls and the getaway: Cars, culture, and the predicament of the gendered space”, 1995, University of Pennsylvania Law Review 144, p. 705-756.

- 11The human resources consulting firm Mercer categorizes the world's capitals in its annual Quality of Living report. This classification is aimed at aiding companies in determining the compensation value for employees sent to work abroad.

- 12Nancy Fraser, Cinzia Arruzza, and Tithi Bhattacharya, "Feminism for the 99%", translated by Mohamed Ramadan, reviewed by Ilham Eidarous, published by Safsafa Publishing House, 2019, electronic version on Abjad application.

- 13A group of authors, "We Buy Everything: Transformations of Housing and Urbanization in Egypt", edited by Yahya Shoukatt and Shahab Ismail, published by Dar Al-Maraya, 2022, electronic version on Abjad application.

Add new comment